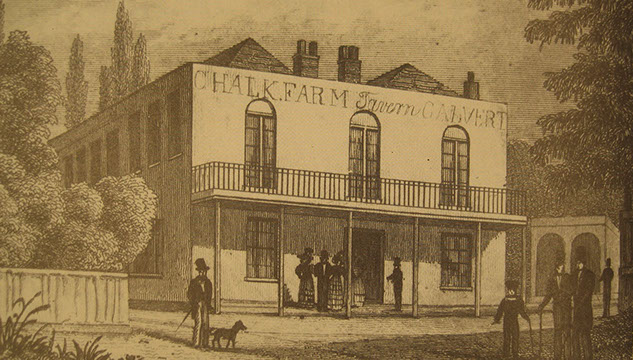

The 17th Century Chalk Farm Tavern was the only building to stand at Primrose Hill until the 1840s.

Image courtesy of the Primrose Hill History website

1 / 2

<

>

Insight

Mixed-Use

Primrose Hill, London

A brief history

Foreword

Our mixed-use scheme on Erskine Road will bring a new vibrancy to the Primrose Hill area. We look at how a wolf-infested forest birthed a new Victorian suburb.

It’s an almost perfect hill: regular, conical, grassy, and rising out of flattish land to 63 metres above sea level. From its well-manicured summit, Primrose Hill affords dramatic views across London, which – together with the area’s pastel-hued Victorian villas, bustling cafés and starry residents – makes this one of London’s best-loved neighbourhoods.

Local people are rightly passionate about preserving its heritage. As a measure of their interest, in 2012 residents fought to keep the name of Dumpton Place, after developers proposed a change to the more fragrant “Jasmin Mews”. Dumpton dates back to 1872, when the road held a coal dump for steam trains. ‘Jasmin Mews’ might sound like modern day Primrose Hill, but it whitewashes an interesting past.

Wilderness Years

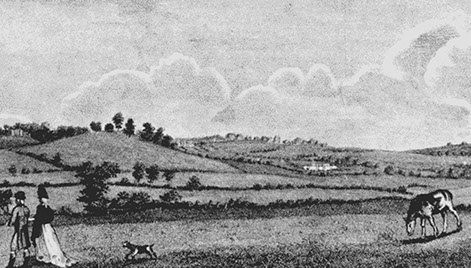

Tracing the area’s history back to Roman times, we find Primrose Hill submerged in the dense, wolf-infested forest northwest of London. Following the Norman conquest, this was named the Forest of Middlesex, and a royal charter gave Londoners the right to hunt its wild deer, ox and boar. Middlesex Forest fell out of royal tenure in the reign of Henry III, and from Mediaeval times the area was gradually denuded and transformed into meadows and open fields, etched by narrow lanes and streams.

Primrose Hill gained its name in Elizabethan times, referencing the abundance of spring flowers found on its slopes. Owned for a time by Lord Southampton, the area became Crown property once again in 1841, and made available to the poor of north London for outdoor recreation.

A New Suburb

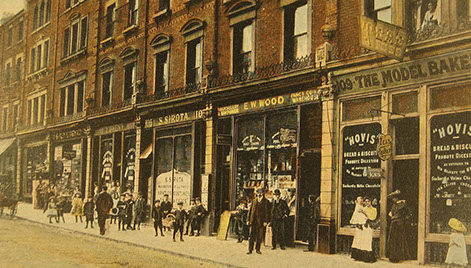

By 1900, Regent’s Park Road was a bustling high street

Image courtesy of the Primrose Hill History website

In the case of Primrose Hill, estate agents are truly misguided when they refer to it as a ‘village’, since this was almost entirely open land until its sudden development as a new London suburb in the 1840s. Before then, just one building of any substance stood in the area – the Chalk Farm Tavern – at what is now No. 89 Regent’s Park Road. The tavern had served refreshments to north-south travellers since at least the 17th Century, and was known for its shooting grounds and pleasure gardens. These facilities occupied the area now delineated by Berkeley Road, Sharpleshall Street and Regent’s Park Road.

In 1820 the Regent’s Canal arrived, followed in 1837 by the London and Birmingham railway, curving northeast out of Euston around Primrose Hill. These two routes delineated what was to become the Primrose Hill Conservation Area.

In 1840 Lord Southampton parcelled up portions of his land for development, and the current street plan was designed. The masterplan featured grand detached and semi-detached villas with big gardens, laid out along sweeping streets. Some of these spacious villas were realised, but London’s rapid growth at the time resulted in the building of terraces instead. By 1870, Primrose Hill was almost complete. While its first residents were respectably well-off, many of the mews set behind the streets housed artisan’s workshops, and the area also became a centre of piano manufacture. Since its inception, Primrose Hill has – and continues to have – its share of commercial activity.

Proud Architecture

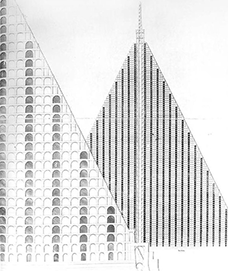

The summit of Primrose Hill has been the location for multiple ambitious but unrealised schemes, including Benjamin Haydon’s 1815 proposal for a replica of The Parthenon. In 1829, Thomas Wilson hoped to alleviate London’s overcrowded cemeteries with a 90-storey high pyramid holding 5 million bodies [image left]. In modern times, the hill’s pristine summit was threatened by (failed) plans to build a 30-foot high replica of Rio de Janeiro statue Christ the Redeemer to publicise the 2016 Rio Olympics.

Image courtesy of the Citylab website

Primrose Hill’s 19th Century buildings include grand rows of listed, narrow houses, symmetrical terraces and large Italianate stuccoed villas. The stucco was originally intended to be left bare, to resemble stone, but today many houses are painted cream or jaunty pastel shades. Homes feature decorative flourishes such as pediments, keystones and scrolled brackets on windows, eves and parapets.

The Conservation Area is not entirely Victorian: it also features contrasting but high quality 20th Century architecture. The strikingly different 1929 Cecil Sharp House was designed in neo-Georgian style by the architect HM Fletcher, while at No. 10 Regent’s Park Road is Modernist icon Erno Goldfinger’s 1955 block of flats. Slotted into a Victorian stuccoed terrace, Goldfinger’s apartments feature large glazed areas, concrete-balustraded balconies and timber-doored garages.

While they make positive contributions to the area, they may not have won planning permission after 1971’s creation of the Conservation Area. Today, it is vital for new developments to take account of the traditional Victorian vernacular while offering confident contemporary interventions that enhance their ancient context.

Related

SUBSCRIBE

Click below to subscribe to our newsletter or to manage your preferences

Subscribe to our newsletter

© 2020 Lyndon Goode Architects Ltd